Imagine the hush falling over the ancient Temple courtyard on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. The air is thick with incense and anticipation. Thousands of Israelites stand in solemn silence, their faces etched with awe and repentance. The High Priest emerges from the Holy of Holies, his white garments radiant under the Jerusalem sun. He has just completed the sacred rituals, standing in the presence of the Divine. Raising his hands to bless the people, he utters the Ineffable Name, the one set apart from all others. In that moment, the crowd falls to the ground in prostration, their voices rising in unison: "Baruch Shem Kavod Malchuto L'Olam Vaed." This phrase, translated as "Blessed be the Name of His glorious kingdom forever and ever," is not a mere echo or repetition of the Name itself. Instead, it honors its holiness by praising the Divine glory without uttering the sacred consonants, revealing the profound separation and reverence embedded in the tradition.

This scene, drawn from ancient Jewish tradition, captures the heart of why God’s personal Name has been treated with such extraordinary reverence in Judaism. As someone who once embraced the Sacred Name movement, seeking to honor Hashem by pronouncing what I thought was the “true” Name, I now see this practice differently. My journey led me to appreciate the wisdom in setting the Name apart, not out of fear or legalism, but out of deep love and humility. If you are a Christian drawn to Hebrew roots, using sounded forms out of a sincere desire to draw closer to God, this article is for you. It is an invitation to explore the biblical and historical truths that reveal why avoidance is the ultimate expression of respect. Let us walk through this together.

Biblical Encouragement to Call Upon the Name

The Bible itself encourages calling upon God’s Name. Verses like Joel 2:32 declare, “Whoever calls on the name of the LORD shall be saved,” a promise echoed throughout Scripture. Psalms urge us to praise and invoke it, as in Psalm 105:1: “Call upon His name.” In early biblical times, the Name was used reverently in oaths, blessings, and daily greetings, such as in Ruth 2:4, where workers exchange “The LORD be with you.” The command in Exodus 20:7 is clear: do not take the Name in vain, meaning falsely or frivolously. This is about proper intent and context, not a prohibition on speaking it at all when done with honor. God reveals aspects of Himself through various names. Elohim for power, El Shaddai for provision, each highlighting divine attributes. The personal Name, tied to the covenant in Exodus 3:14-15, signifies eternal existence: “I AM WHO I AM.”

A Shift Born of Reverence and Protection

Yet, over time, a shift occurred. During the Babylonian Exile around the sixth century BCE, Jews faced cultures that invoked divine names in magic or idolatry, a practice that sounded all too familiar and posed a real risk of profanation. To safeguard against any misuse, they began substituting “Adonai,” meaning “my Lord,” when reading aloud. This was not about losing the Name but protecting it. By the Second Temple period, this caution deepened. The Name was pronounced only in the Temple, and even there, sparingly. On Yom Kippur, the High Priest spoke it during confessions and the Priestly Blessing in Numbers 6:24-27. The people’s prostration and chant of “Baruch Shem” was not just a reaction; it was a deliberate affirmation that amplified the Name’s sanctity, acknowledging its glory without repeating it. This response, absent in modern Sacred Name practices, underscores how set apart it truly is. Treating it as everyday speech misses this layer of awe.

The Risk That Persists Today

Tragically, this risk persists in our time. Today, the Name or its approximations is often heard in casual curses on screens and streets: as an exclamation of surprise, as frustration, or tossed out without thought. These have become so commonplace that they barely register as profane anymore, yet they reduce the Divine to an empty expression. Even more troubling, in modern occult, New Age, and pagan practices, elements of the Name appear in spells, invocations, talismans, and rituals, sometimes blended with other deities or used to harness power for personal will. Such uses, whether frivolous or manipulative, echo the very dangers our ancestors guarded against during the Exile.

The Torah itself is crystal clear about who alone saves and upon whom we call in times of deliverance. Consider Exodus 15:2: “Yah is my strength and song, and He has become my salvation.” Or Deuteronomy 32:39: “See now that I, even I, am He, and there is no god beside Me; I kill and I make alive; I wound and I heal; and there is none that can deliver out of My hand.” Joel 2:32 declares plainly: “And it shall come to pass that everyone who calls on the name of the LORD shall be saved.” These verses, rooted in the Torah and Prophets, affirm that salvation belongs exclusively to Hashem, the One whose Name we are commanded to call upon in trust and awe. Any blurring of that unique role risks diminishing the absolute oneness and saving power the Torah ascribes solely to Him. The tradition of substitution protects this truth, keeping our focus on the transcendent Source rather than any created intermediary.

The tradition of substitution, then, is not outdated caution but timeless wisdom: better to honor through restraint than to expose the sacred to everyday desecration.

Scribal Clues That Point Away from Pronunciation

Many who study Hebrew roots and manuscripts, including Karaite scholar Nehemia Gordon, point to medieval texts where vowel points appear under the consonants, suggesting pronunciations like Yehov**. They sometimes argue this preserves the original sound. However, this interpretation remains a minority view, even among Karaites, who emphasize literal reading of the Torah and reject Rabbinic oral traditions. Traditional Karaite practice, like mainstream Judaism, generally protects the Name by substituting “Adonai” during reading or “HaShem” in speech, treating it as too sacred for casual utterance. The Karaite Jews of America, for example, maintain this reverence in their liturgy and teachings, using substitutes to honor the Name’s holiness.

But here is a key insight: those vowel points do not reveal the true pronunciation; they point away from it, serving as a cue for substitution. This system, called Qere-Ketiv what is written versus what is read, was developed by Masoretic scribes between the sixth and tenth centuries CE to guide oral reading of the unvoweled Hebrew text. For the Name’s consonants, they inserted vowels from “Adonai,” a shewa, cholam, and kamatz, to signal: read “Adonai” here.

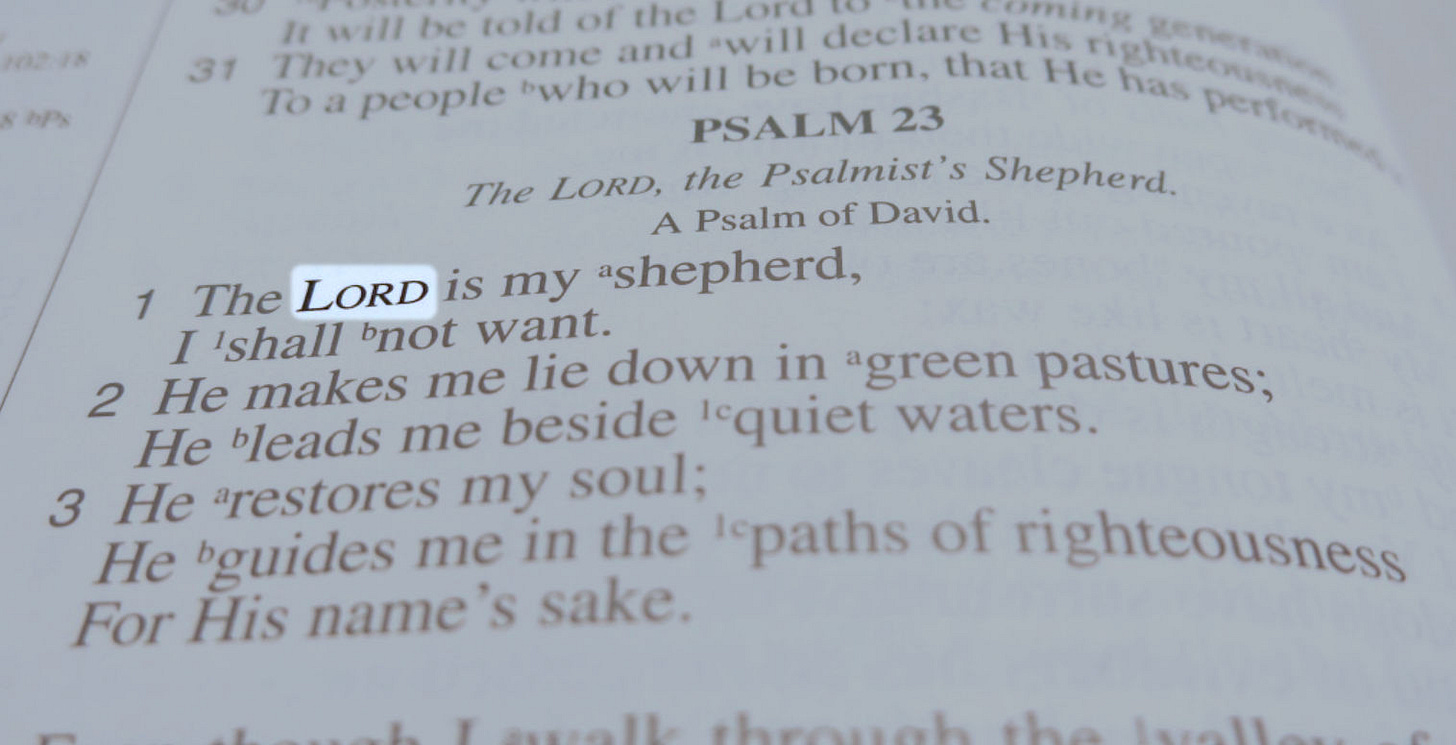

A related clue appears in our English Bibles today. When you see “LORD” printed in all capital letters (or small caps) in the Old Testament, it is not a random style choice. It is the translators’ way of signaling that the original Hebrew has the Tetragrammaton, Yud Hey to the Vav Hey. In contrast, “Lord” (with only the first letter capitalized) usually translates “Adonai.” This convention, used in most major English versions like the KJV, NIV, and ESV, preserves the ancient Jewish custom of substituting “Adonai” for the Name during reading. It began with the Septuagint’s use of “Kyrios” (Lord) and carried forward into English to respect the tradition of not pronouncing the sacred Name aloud. Far from erasing the Name, the all-caps “LORD” quietly reminds readers of its presence and holiness every time it appears, over 6,800 times in the Old Testament.

Hebrew texts are rich with such scribal hints and clues, designed to ensure accurate transmission and interpretation. Beyond vowel points, cantillation marks known as ta’amim or tropes provide musical notation, punctuation, and emphasis. These symbols, like the etnachta (a pause similar to a comma) or the sof pasuk (a full stop), guide the chanter in synagogues, dividing verses into logical units and preventing misreadings. For instance, in complex sentences, tropes act as invisible commas or accents, much like how a misplaced pause can change meaning in spoken English. In the context of the Name, these elements reinforce the oral tradition, where the written text hints at what to say without spelling it out fully, preserving sanctity through subtlety.

A striking example illuminates this. In phrases like “Adonai followed by the Name,” such as in Ezekiel 2:4, the text avoids an awkward double “Adonai Adonai.” Instead, the vowels shift to those of “Elohim,” creating a hybrid that reads oddly as Yehovih. English Bibles translate this as “Lord GOD,” with “GOD” in capitals to indicate the substitution. This is no accident; it is proof of intentional avoidance. If the points were meant for literal pronunciation, why the switch? Scholars across Jewish and Christian traditions agree this creates “ghost words,” not authentic sounds. The form “Jehov**,” popularized in the Middle Ages, arose when Christian translators misunderstood this cue, combining the consonants with Adonai’s vowels literally. It is a well-meaning mix-up, not a divine revelation.

Do We Truly Know the Pronunciation?

So, do we truly have no idea how to pronounce it? In a sense, yes for public use. The exact ancient sound was deliberately obscured to prevent profanation. Even when referring to the letters themselves, many in Orthodox tradition use extra caution, such as saying “Yud Kay Vav Kay” instead of “Yud Hey to the Vav Hey,” to avoid any sound that might approach the sacred combination. In this article, and even in our instructions for writing it, we use care by referring to it as Yud Hey to the Vav Hey without vowels or attempts at sound. Any combination of sounds formed from these letters remains a matter of deep reverence, not casual reconstruction. Among priestly families, or Kohanim, tradition holds that the pronunciation may be handed down orally for rare or future Temple use, but it remains guarded. The focus is not on reconstructing it but on honoring its mystery. Kabbalistic teachings add depth: the letters Yud Hey to the Vav Hey represent creation’s blueprint, with cosmic power. Speaking it casually could misuse, like handling a sacred artifact with muddy hands.

This reverence extends to writing. In sacred texts, the consonants appear fully, but in everyday contexts, many write “G-d” or use “HaShem” The Name to symbolize caution. For this article, distant from the holiness of Hashem’s word, we refer to it as Yud Hey to the Vav Hey without vowels or attempts at sound, preserving that separation.

A Personal Picture of Reverence

For Christians, this might seem counterintuitive. After all, the New Testament uses “Kyrios” Lord for the Name, following the Septuagint’s Greek translation. Jesus and the apostles invoked God faithfully without insisting on phonetics. The command to call upon the Name is about relationship and ethical living, kiddush HaShem, sanctifying the Name through actions not exact pronunciation. Salvation comes from intent, not sounds, freeing us from fear of “getting it wrong.”

Think for a moment about your own earthly father. I never called my dad by his first name, Ernie. It was always Dad, Father, or on those rare occasions when respect demanded extra weight, Sir. Picture a Little League game: my dad coaching third base, me out in right field (okay, maybe not the pitcher’s mound, but the position doesn’t matter). If he shouted instructions “play deep” and I yelled back, “Yes, Ernie!” every head on the field would have turned in shock. Would my father have felt honored by that casual familiarity? Or would he have felt a quiet shame, as if the unique bond between father and son had been reduced to something ordinary? The most intimate titles Dad, Father carried the deepest respect precisely because they were not his everyday name. They signified relationship, authority, and love all at once. In the same way, substituting Adonai my Lord or HaShem The Name does not distance us from Hashem; it draws us closer through humble reverence, honoring the transcendent Father in a manner worthy of His glory.

An Invitation to Humble Reverence

If your heart leads you to Hebrew roots out of love for Hashem, consider this: the greatest honor might lie in echoing our ancestors’ humility. By setting the Name apart, we acknowledge its transcendence, beyond human grasp. The Yom Kippur scene reminds us that true closeness comes through awe, not familiarity. Let us unite in this reverence, blessing His glorious kingdom forever.